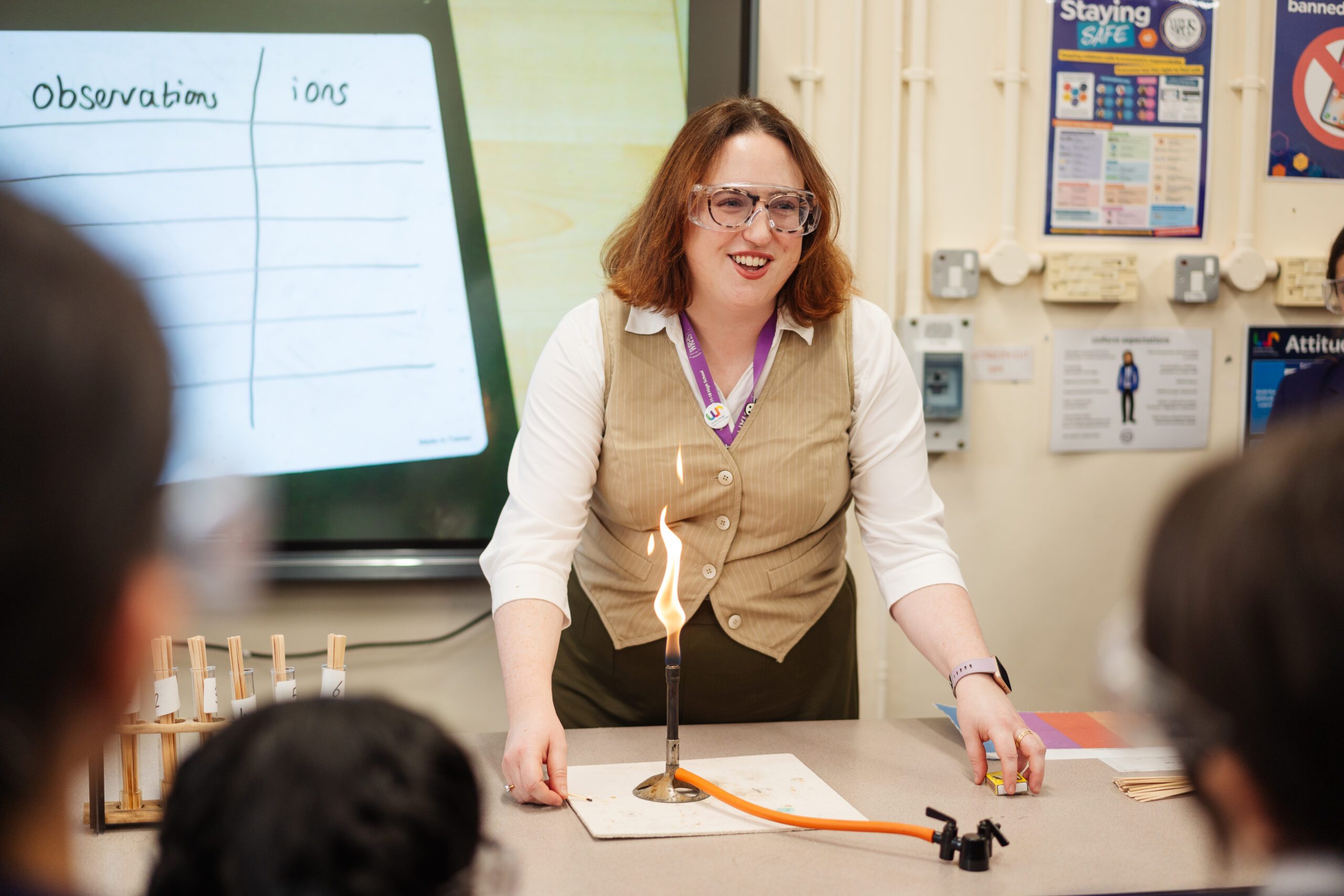

Emily Bird is Head of Science at an inner-city school in Manchester, where she teaches A-level biology, BTEC applied science, GCSE, and KS3 science. She has also worked as an examiner for over ten years. She is passionate about supporting girls and women into STEM. Find her on X (@missbird90) or Threads (@missbird_90).

Mini whiteboards are a brilliant way of increasing the think participation ratio while checking for understanding, but it is only worth gaining that information if you are going to change the lesson as a result. Knowing what to do next with different whole class responses can increase the pace, and more importantly the understanding, within a lesson.

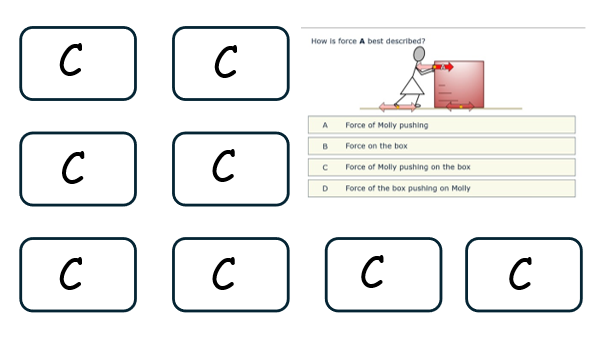

Firstly I ensure my class know my routine for using MWB. The quality of what happens next depends on the quality of the question: STEM learn’s BEST resources (https://www.stem.org.uk/secondary/resources/collections/science/best-evidence-science-teaching) include many pre-made diagnostic questions for KS3 and 4. I’m going to use one of their examples here to look at five common scenarios and what I would do next to build understanding in the classroom.

Imagine this is one in a series of questions I’m asking a class after teaching them about Newtons’s 3rd law of motion. The correct answer here is C, A and B are not wrong, but are incomplete answers. D is a description of the reaction force.

Scenario 1:

All of the class have answered correctly.

I would cold call a student to ask how they know this is the correct answer, and then I would move on. Regardless of how many other questions I had prepared, if the class already understand the concept I am wasting time by asking them again. Instead I would either ask a more challenging question, a question about a different concept or I would simply praise the class and move on to the next part of the lesson.

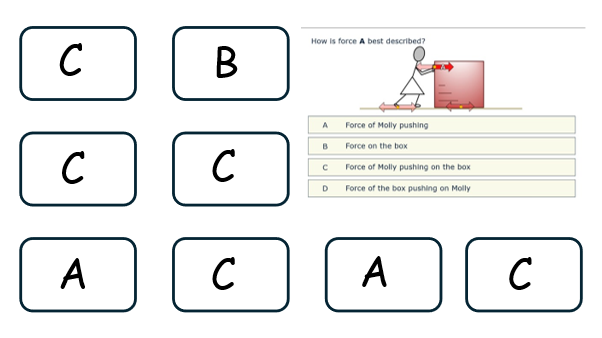

Scenario 2:

Most of the class are correct, but crucially, no one is wrong: A and B are incomplete not incorrect.

I would collect a few boards. Holding up a board with A I would ask a person with a “C” board to explain why they chose C and not A. This might take a couple of questions to elicit the correct response, and it relies on having a culture of no opt out in the classroom. I would follow this up by an “A” why C is a better answer than B. I’d also ask another question to the whole class to check they now understand this. Later, when the class are completing independent work I would check on the A and B students to see if they need support and offer praise if they are now showing better understanding.

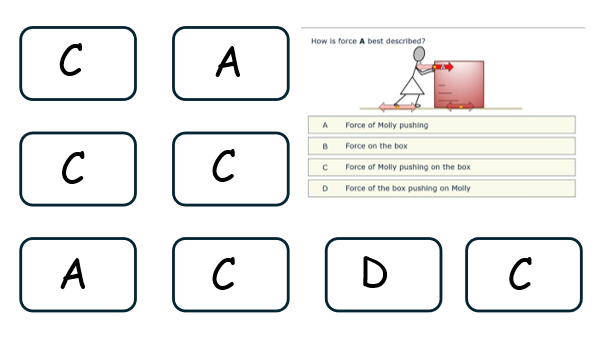

Scenario 3:

Mixture of correct, partially correct and incorrect.

I would cold call one of the students who selected C, and ask them why D is an incorrect answer. I might then ask the student who put D why A is incomplete to check that they have understood the reasoning. Again, I might ask another question to the whole class, or I might check in on the student who put D later in the lesson.

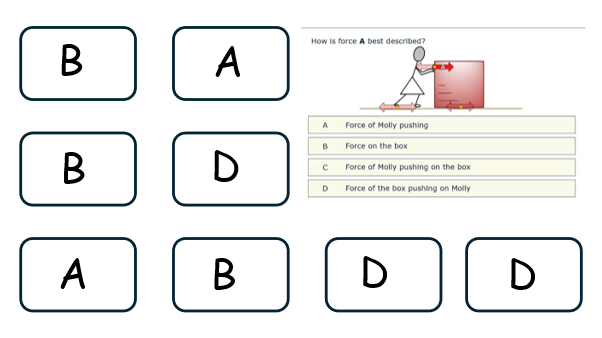

Scenario 4:

All incorrect.

If all or the majority are wrong, questioning the students risks spreading misconceptions and wastes time. Instead, I would get them to put their whiteboards down, and I would re-teach Newton’s third law.

I might ask the same question again when I’d re-taught it or might change this slightly to ask them to explain why A/B/D isn’t the answer.

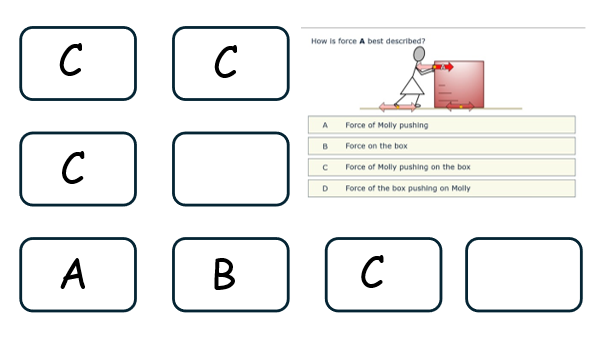

Scenario 5:

Some students haven’t put an answer. Sometimes this might be a “?” instead of a blank.

There are a few different ways to approach this, depending on the age and stage of the students.

Sometimes just stating that some students haven’t had time to write an answer yet, and so I’m giving them more time might be appropriate. If students haven’t answered because they think they can get away with not answering, sometimes just reminding them that they are accountable is enough.

For older students I might explain why I need them to answer, even if they guess. I explain that this is so thatI can see their thought process to help them to understand.

For less confident students it might be best to add in a think pair share step as a scaffold before writing their own answers. Explaining “we thought” can be easier than “I think” while you are building up to a no opt out classroom.

In summary:

Asking questions

- Have a routine

- Use planned, diagnostic questions

- Work towards a culture of no opt out

Using answers:

- All correct – make the questions more challenging or move on

- Some misconceptions – use questioning to address these

- Many answers are wrong – stop and reteach the content